Tag: Stephen King

Autopsy Room Four ( story ) … Stephen King

The concept, a living man lying on a gurney as pathologists unknowingly prepare to perform an autopsy on him, is creepy and intriguing. It’s Stephen King’s flippant handling of it that disappoints.

A story like this should be ominous. Instead the “dead” man, who’s fully conscious but also fully paralyzed, makes corny wisecracks to himself, even as his body is about to be sawed open and dismantled.

my rating : 2 of 5

1997

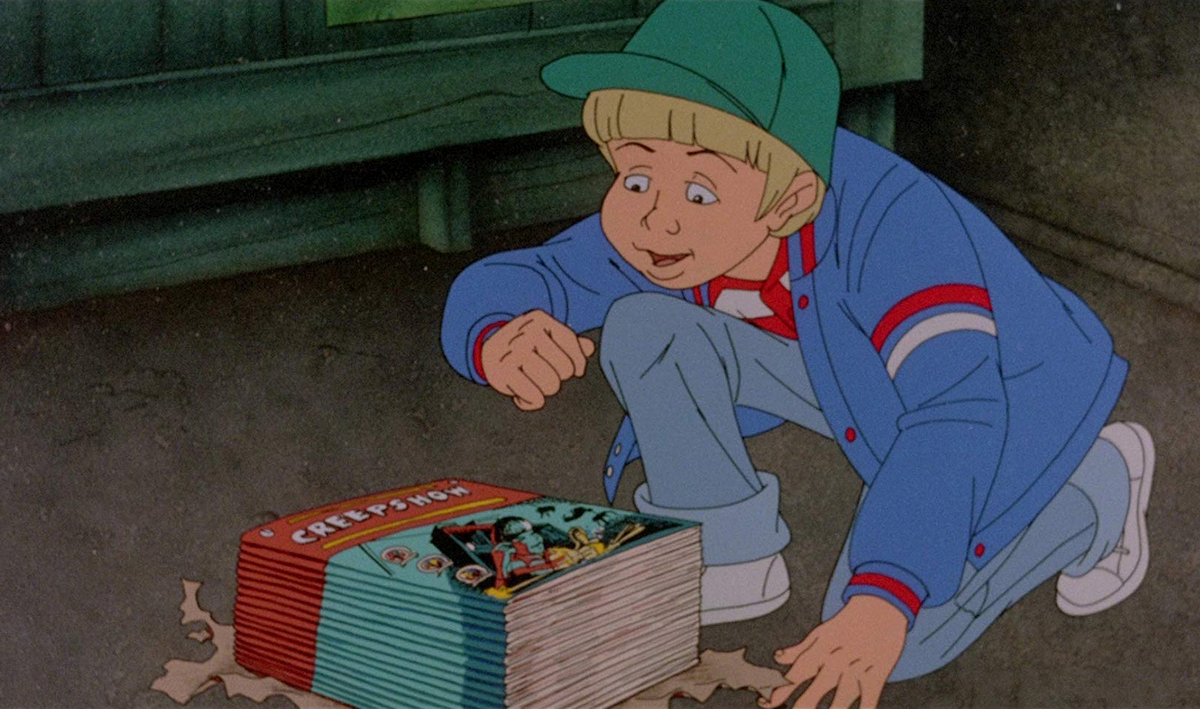

video review : Creepshow 2

This show is better than the first. The Old Chief bit is dumb, but The Raft; a cross between The Blob, Jaws and Cujo; is interesting. It has four partiers stranded in a lake at the mercy of killer slime.

The best story is the final one, about a woman who accidentally kills a Hitchhiker on her way home from having sex with someone other than her husband. It’s the one tale that is truly creepy.

my rating : 3 of 5

1987

One For The Road ( story ) … Stephen King

It was quarter past ten and Herb Tooklander was thinking of closing for the night when the man in the fancy overcoat and the white, staring face burst into Tookey’s Bar, which lies in the northern part of Falmouth. It was the tenth of January, just about the time most folks are learning to live comfortably with all the New Year’s resolutions they broke, and there was one hell of a northeaster blowing outside. Six inches had come down before dark and it had been going hard and heavy since then. Twice we had seen Billy Larribee go by high in the cab of the town plow, and the second time Tookey ran him out a beer-an act of pure charity my mother would have called it, and my God knows she put down enough of Tookey’s beer in her time. Billy told him they were keeping ahead of it on the main road, but the side ones were closed and apt to stay that way until next morning. The radio in Portland was forecasting another foot and a forty-mile-an-hour wind to pile up the drifts.

There was just Tookey and me in the bar, listening to the wind howl around the eaves and watching it dance the fire around on the hearth. “Have one for the road, Booth,” Tookey says, “I’m gonna shut her down.”

He poured me one and himself one and that’s when the door cracked open and this stranger staggered in, snow up to his shoulders and in his hair, like he had rolled around in confectioner’s sugar. The wind billowed a sand-fine sheet of snow in after him.

“Close the door!” Tookey roars at him. “Was you born in a barn?”

I’ve never seen a man who looked that scared. He was like a horse that’s spent an afternoon eating fire nettles. His eyes rolled toward Tookey and he said, “My wife-my daughter-” and he collapsed on the floor in a dead faint.

“Holy Joe,” Tookey says. “Close the door, Booth, would you?”

I went and shut it, and pushing it against the wind was something of a chore. Tookey was down on one knee holding the fellow’s head up and patting his cheeks. I got over to him and saw right off that it was nasty. His face was fiery red, but there were gray blotches here and there, and when you’ve lived through winters in Maine since the time Woodrow Wilson was President, as I have, you know those gray blotches mean frostbite.

“Fainted,” Tookey said. “Get the brandy off the backbar, will you?”

I got it and came back. Tookey had opened the fellow’s coat. He had come around a little; his eyes were half open and he was muttering something too low to catch.

“Pour a capful,” Tookey says.

“Just a cap?” I asks him.

“That stuff’s dynamite,” Tookey says. “No sense overloading his carb.”

I poured out a capful and looked at Tookey. He nodded. “Straight down the hatch.”

I poured it down. It was a remarkable thing to watch. The man trembled all over and began to cough. His face got redder. His eyelids, which had been at half-mast, flew up like window shades. I was a bit alarmed, but Tookey only sat him up like a big baby and clapped him on the back.

The man started to retch, and Tookey clapped him again.

“Hold onto it,” he says, “that brandy comes dear.”

The man coughed some more, but it was diminishing now. I got my first good look at him. City fellow, all right, and from somewhere south of Boston, at a guess. He was wearing kid gloves, expensive but thin. There were probably some more of those grayish-white patches on his hands, and he would be lucky not to lose a finger or two. His coat was fancy, all right; a three-hundred-dollar job if ever I’d seen one. He was wearing tiny little boots that hardly came up over his ankles, and I began to wonder about his toes.

“Better,” he said.

“All right,” Tookey said. “Can you come over to the fire?”

“My wife and my daughter,” he said. “They’re out there… in the storm.”

“From the way you came in, I didn’t figure they were at home watching the TV,” Tookey said. “You can tell us by the fire as easy as here on the floor. Hook on, Booth.”

He got to his feet, but a little groan came out of him and his mouth twisted down in pain. I wondered about his toes again, and I wondered why God felt he had to make fools from New York City who would try driving around in southern Maine at the height of a northeast blizzard. And I wondered if his wife and his little girl were dressed any warmer than him.

We hiked him across to the fireplace and got him sat down in a rocker that used to be Missus Tookey’s favorite until she passed on in ’74. It was Missus Tookey that was responsible for most of the place, which had been written up in Down East and the Sunday Telegram and even once in the Sunday supplement of the Boston Globe. It’s really more of a public house than a bar, with its big wooden floor, pegged together rather than nailed, the maple bar, the old barn-raftered ceiling, and the monstrous big fieldstone hearth. Missus Tookey started to get some ideas in her head after the Down East article came out, wanted to start calling the place Tookey’s Inn or Tookey’s Rest, and I admit it has sort of a Colonial ring to it, but I prefer plain old Tookey’s Bar. It’s one thing to get uppish in the summer, when the state’s full of tourists, another thing altogether in the winter, when you and your neighbors have to trade together. And there had been plenty of winter nights, like this one, that Tookey and I had spent all alone together, drinking scotch and water or just a few beers. My own Victoria passed on in ’73, and Tookey’s was a place to go where there were enough voices to mute the steady ticking of the deathwatch beetle-even if there was just Tookey and me, it was enough. I wouldn’t have felt the same about it if the place had been Tookey’s Rest. It’s crazy but it’s true.

We got this fellow in front of the fire and he got the shakes harder than ever. He hugged onto his knees and his teeth clattered together and a few drops of clear mucus spilled off the end of his nose. I think he was starting to realize that another fifteen minutes out there might have been enough to kill him. It’s not the snow, it’s the wind-chill factor. It steals your heat.

“Where did you go off the road?” Tookey asked him.

“S-six miles s-s-south of h-here,” he said.

Tookey and I stared at each other, and all of a sudden I felt cold. Cold all over.

“You sure?” Tookey demanded. “You came six miles through the snow?”

He nodded. “I checked the odometer when we came through t-town. I was following directions… going to see my wife’s s-sister… in Cumberland… never been there before… we’re from New Jersey…”

New Jersey. If there’s anyone more purely foolish than a New Yorker it’s a fellow from New Jersey.

“Six miles, you’re sure?” Tookey demanded.

“Pretty sure, yeah. I found the turnoff but it was drifted in… it was…”

Tookey grabbed him. In the shifting glow of the fire his face looked pale and strained, older than his sixty-six years by ten. “You made a right turn?”

“Right turn, yeah. My wife-”

“Did you see a sign?”

“Sign?” He looked up at Tookey blankly and wiped the end of his nose. “Of course I did. It was on my instructions. Take Jointner Avenue through Jerusalem’s Lot to the 295 entrance ramp.” He looked from Tookey to me and back to Tookey again. Outside, the wind whistled and howled and moaned through the eaves. “Wasn’t that right, mister?”

“The Lot,” Tookey said, almost too soft to hear. “Oh my God.”

“What’s wrong?” the man said. His voice was rising. “Wasn’t that right? I mean, the road looked drifted in, but I thought… if there’s a town there, the plows will be out and… and then I…”

He just sort of tailed off.

“Booth,” Tookey said to me, low. “Get on the phone. Call the sheriff.”

“Sure,” this fool from New Jersey says, “that’s right. What’s wrong with you guys, anyway? You look like you saw a ghost.”

Tookey said, “No ghosts in the Lot, mister. Did you tell them to stay in the car?”

“Sure I did,” he said, sounding injured. “I’m not crazy.”

Well, you couldn’t have proved it by me.

“What’s your name?” I asked him. “For the sheriff.”

“Lumley,” he says. “Gerard Lumley.”

He started in with Tookey again, and I went across to the telephone. I picked it up and heard nothing but dead silence. I hit the cutoff buttons a couple of times. Still nothing.

I came back. Tookey had poured Gerard Lumley another tot of brandy, and this one was going down him a lot smoother.

“Was he out?” Tookey asked.

“Phone’s dead.”

“Hot damn,” Tookey says, and we look at each other. Outside the wind gusted up, throwing snow against the windows.

Lumley looked from Tookey to me and back again.

“Well, haven’t either of you got a car?” he asked. The anxiety was back in his voice. “They’ve got to run the engine to run the heater. I only had about a quarter of a tank of gas, and it took me an hour and a half to… Look, will you answer me?” He stood up and grabbed Tookey’s shirt.

“Mister,” Tookey says, “I think your hand just ran away from your brains, there.”

Lumley looked at his hand, at Tookey, then dropped it. “Maine,” he hissed. He made it sound like a dirty word about somebody’s mother. “All right,” he said. “Where’s the nearest gas station? They must have a tow truck-”

“Nearest gas station is in Falmouth Center,” I said. “That’s three miles down the road from here.”

“Thanks,” he said, a bit sarcastic, and headed for the door, buttoning his coat.

“Won’t be open, though,” I added.

He turned back slowly and looked at us.

“What are you talking about, old man?”

“He’s trying to tell you that the station in the Center belongs to Billy Larribee and Billy’s out driving the plow, you damn fool,” Tookey says patiently. “Now why don’t you come back here and sit down, before you bust a gut?”

He came back, looking dazed and frightened. “Are you telling me you can’t… that there isn’t…?”

“I ain’t telling you nothing,” Tookey says. “You’re doing all the telling, and if you stopped for a minute, we could think this over.”

“What’s this town, Jerusalem’s Lot?” he asked. “Why was the road drifted in? And no lights on anywhere?”

I said, “Jerusalem’s Lot burned out two years back.”

“And they never rebuilt?” He looked like he didn’t believe it.

“It appears that way,” I said, and looked at Tookey. “What are we going to do about this?”

“Can’t leave them out there,” he said.

I got closer to him. Lumley had wandered away to look out the window into the snowy night.

“What if they’ve been got at?” I asked.

“That may be,” he said. “But we don’t know it for sure. I’ve got my Bible on the shelf. You still wear your Pope’s medal?”

I pulled the crucifix out of my shirt and showed him. I was born and raised Congregational, but most folks who live around the Lot wear something-crucifix, St. Christopher’s medal, rosary, something. Because two years ago, in the span of one dark October month, the Lot went bad. Sometimes, late at night, when there were just a few regulars drawn up around Tookey’s fire, people would talk it over. Talk around it is more like the truth. You see, people in the Lot started to disappear. First a few, then a few more, than a whole slew. The schools closed. The town stood empty for most of a year. Oh, a few people moved in-mostly damn fools from out of state like this fine specimen here-drawn by the low property values, I suppose. But they didn’t last. A lot of them moved out a month or two after they’d moved in. The others… well, they disappeared. Then the town burned flat. It was at the end of a long dry fall. They figure it started up by the Marsten House on the hill that overlooked Jointner Avenue, but no one knows how it started, not to this day. It burned out of control for three days. After that, for a time, things were better. And then they started again.

I only heard the word “vampires” mentioned once. A crazy pulp truck driver named Richie Messina from over Freeport way was in Tookey’s that night, pretty well liquored up. “Jesus Christ,” this stampeder roars, standing up about nine feet tall in his wool pants and his plaid shirt and his leather-topped boots. “Are you all so damn afraid to say it out? Vampires! That’s what you’re all thinking, ain’t it? Jesus-jumped-up-Christ in a chariot-driven sidecar! Just like a bunch of kids scared of the movies! You know what there is down there in ‘Salem’s Lot? Want me to tell you? Want me to tell you?”

“Do tell, Richie,” Tookey says. It had got real quiet in the bar. You could hear the fire popping, and outside the soft drift of November rain coming down in the dark. “You got the floor.”

“What you got over there is your basic wild dog pack,” Richie Messina tells us. “That’s what you got. That and a lot of old women who love a good spook story. Why, for eighty bucks I’d go up there and spend the night in what’s left of that haunted house you’re all so worried about. Well, what about it? Anyone want to put it up?”

But nobody would. Richie was a loudmouth and a mean drunk and no one was going to shed any tears at his wake, but none of us were willing to see him go into ‘Salem’s Lot after dark.

“Be screwed to the bunch of you,” Richie says. “I got my four-ten in the trunk of my Chevy, and that’ll stop anything in Falmouth, Cumberland, or Jerusalem’s Lot. And that’s where I’m goin’.”

He slammed out of the bar and no one said a word for a while. Then Lamont Henry says, real quiet, “That’s the last time anyone’s gonna see Richie Messina. Holy God.” And Lamont, raised to be a Methodist from his mother’s knee, crossed himself.

“He’ll sober off and change his mind,” Tookey said, but he sounded uneasy. “He’ll be back by closin’ time, makin’ out it was all a joke.”

But Lamont had the right of that one, because no one ever saw Richie again. His wife told the state cops she thought he’d gone to Florida to beat a collection agency, but you could see the truth of the thing in her eyes-sick, scared eyes. Not long after, she moved away to Rhode Island. Maybe she thought Richie was going to come after her some dark night. And I’m not the man to say he might not have done.

Now Tookey was looking at me and I was looking at Tookey as I stuffed my crucifix back into my shirt. I never felt so old or so scared in my life.

Tookey said again, “We can’t just leave them out there, Booth.”

“Yeah. I know.”

We looked at each other for a moment longer, and then he reached out and gripped my shoulder. “You’re a good man, Booth.” That was enough to buck me up some. It seems like when you pass seventy, people start forgetting that you are a man, or that you ever were.

Tookey walked over to Lumley and said, “I’ve got a four-wheel-drive Scout. I’ll get it out.”

“For God’s sake, man, why didn’t you say so before?” He had whirled around from the window and was staring angrily at Tookey. “Why’d you have to spend ten minutes beating around the bush?”

Tookey said, very softly, “Mister, you shut your jaw. And if you get the urge to open it, you remember who made that turn onto an unplowed road in the middle of a goddamned blizzard.”

He started to say something, and then shut his mouth. Thick color had risen up in his cheeks. Tookey went out to get his Scout out of the garage. I felt around under the bar for his chrome flask and filled it full of brandy. Figured we might need it before this night was over.

Maine blizzard-ever been out in one?

The snow comes flying so thick and fine that it looks like sand and sounds like that, beating on the sides of your car or pickup. You don’t want to use your high beams because they reflect off the snow and you can’t see ten feet in front of you. With the low beams on, you can see maybe fifteen feet. But I can live with the snow. It’s the wind I don’t like, when it picks up and begins to howl, driving the snow into a hundred weird flying shapes and sounding like all the hate and pain and fear in the world. There’s death in the throat of a snowstorm wind, white death-and maybe something beyond death. That’s no sound to hear when you’re tucked up all cozy in your own bed with the shutters bolted and the doors locked. It’s that much worse if you’re driving. And we were driving smack into ‘Salem’s Lot.

“Hurry up a little, can’t you?” Lumley asked.

I said, “For a man who came in half frozen, you’re in one hell of a hurry to end up walking again.”

He gave me a resentful, baffled look and didn’t say anything else. We were moving up the highway at a steady twenty-five miles an hour. It was hard to believe that Billy Larribee had just plowed this stretch an hour ago; another two inches had covered it, and it was drifting in. The strongest gusts of wind rocked the Scout on her springs. The headlights showed a swirling white nothing up ahead of us. We hadn’t met a single car.

About ten minutes later Lumley gasps: “Hey! What’s that?”

He was pointing out my side of the car; I’d been looking dead ahead. I turned, but was a shade too late. I thought I could see some sort of slumped form fading back from the car, back into the snow, but that could have been imagination.

“What was it? A deer?” I asked.

“I guess so,” he says, sounding shaky. “But its eyes-they looked red.” He looked at me. “Is that how a deer’s eyes look at night?” He sounded almost as if he were pleading.

“They can look like anything,” I says, thinking that might be true, but I’ve seen a lot of deer at night from a lot of cars, and never saw any set of eyes reflect back red.

Tookey didn’t say anything.

About fifteen minutes later, we came to a place where the snowbank on the right of the road wasn’t so high because the plows are supposed to raise their blades a little when they go through an intersection.

“This looks like where we turned,” Lumley said, not sounding too sure about it. “I don’t see the sign-”

“This is it,” Tookey answered. He didn’t sound like himself at all. “You can just see the top of the signpost.”

“Oh. Sure.” Lumley sounded relieved. “Listen, Mr. Tooklander, I’m sorry about being so short back there. I was cold and worried and calling myself two hundred kinds of fool. And I want to thank you both-”

“Don’t thank Booth and me until we’ve got them in this car,” Tookey said. He put the Scout in four-wheel drive and slammed his way through the snowbank and onto Jointner Avenue, which goes through the Lot and out to 295. Snow flew up from the mudguards. The rear end tried to break a little bit, but Tookey’s been driving through snow since Hector was a pup. He jockeyed it a bit, talked to it, and on we went. The headlights picked out the bare indication of other tire tracks from time to time, the ones made by Lumley’s car, and then they would disappear again. Lumley was leaning forward, looking for his car. And all at once Tookey said, “Mr. Lumley.”

“What?” He looked around at Tookey.

“People around these parts are kind of superstitious about ‘Salem’s Lot,” Tookey says, sounding easy enough-but I could see the deep lines of strain around his mouth, and the way his eyes kept moving from side to side. “If your people are in the car, why, that’s fine. We’ll pack them up, go back to my place, and tomorrow, when the storm’s over, Billy will be glad to yank your car out of the snowbank. But if they’re not in the car-”

“Not in the car?” Lumley broke in sharply. “Why wouldn’t they be in the car?”

“If they’re not in the car,” Tookey goes on, not answering, “we’re going to turn around and drive back to Falmouth Center and whistle for the sheriff. Makes no sense to go wallowing around at night in a snowstorm anyway, does it?”

“They’ll be in the car. Where else would they be?”

I said, “One other thing, Mr. Lumley. If we should see anybody, we’re not going to talk to them. Not even if they talk to us. You understand that?”

Very slow, Lumley says, “Just what are these superstitions?”

Before I could say anything-God alone knows what I would have said-Tookey broke in. “We’re there.”

We were coming up on the back end of a big Mercedes. The whole hood of the thing was buried in a snowdrift, and another drift had socked in the whole left side of the car. But the taillights were on and we could see exhaust drifting out of the tailpipe.

“They didn’t run out of gas, anyway,” Lumley said.

Tookey pulled up and pulled on the Scout’s emergency brake. “You remember what Booth told you, Lumley.”

“Sure, sure.” But he wasn’t thinking of anything but his wife and daughter. I don’t see how anybody could blame him, either.

“Ready, Booth?” Tookey asked me. His eyes held on mine, grim and gray in the dashboard lights.

“I guess I am,” I said.

We all got out and the wind grabbed us, throwing snow in our faces. Lumley was first, bending into the wind, his fancy topcoat billowing out behind him like a sail. He cast two shadows, one from Tookey’s headlights, the other from his own taillights. I was behind him, and Tookey was a step behind me. When I got to the trunk of the Mercedes, Tookey grabbed me.

“Let him go,” he said.

“Janey! Francie!” Lumley yelled. “Everything okay?” He pulled open the driver’s-side door and leaned in. “Everything-”

He froze to a dead stop. The wind ripped the heavy door right out of his hand and pushed it all the way open.

“Holy God, Booth,” Tookey said, just below the scream of the wind. “I think it’s happened again.”

Lumley turned back toward us. His face was scared and bewildered, his eyes wide. All of a sudden he lunged toward us through the snow, slipping and almost falling. He brushed me away like I was nothing and grabbed Tookey.

“How did you know?” he roared. “Where are they? What the hell is going on here?”

Tookey broke his grip and shoved past him. He and I looked into the Mercedes together. Warm as toast it was, but it wasn’t going to be for much longer. The little amber low-fuel light was glowing. The big car was empty. There was a child’s Barbie doll on the passenger’s floormat. And a child’s ski parka was crumpled over the seatback.

Tookey put his hands over his face… and then he was gone. Lumley had grabbed him and shoved him right back into the snowbank. His face was pale and wild. His mouth was working as if he had chewed down on some bitter stuff he couldn’t yet unpucker enough to spit out. He reached in and grabbed the parka.

“Francie’s coat?” he kind of whispered. And then loud, bellowing:

“Francie’s coat!” He turned around, holding it in front of him by the little fur-trimmed hood. He looked at me, blank and unbelieving. “She can’t be out without her coat on, Mr. Booth. Why… why… she’ll freeze to death.”

“Mr. Lumley-”

He blundered past me, still holding the parka, shouting:

“Francie! Janey! Where are you? Where are youuu?”

I gave Tookey my hand and pulled him onto his feet. “Are you all-”

“Never mind me,” he says. “We’ve got to get hold of him, Booth.”

We went after him as fast as we could, which wasn’t very fast with the snow hip-deep in some places. But then he stopped and we caught up to him.

“Mr. Lumley-” Tookey started, laying a hand on his shoulder.

“This way,” Lumley said. “This is the way they went. Look!”

We looked down. We were in a kind of dip here, and most of the wind went right over our heads. And you could see two sets of tracks, one large and one small, just filling up with snow. If we had been five minutes later, they would have been gone.

He started to walk away, his head down, and Tookey grabbed him back. “No! No, Lumley!”

Lumley turned his wild face up to Tookey’s and made a fist. He drew it back… but something in Tookey’s face made him falter. He looked from Tookey to me and then back again.

“She’ll freeze,” he said, as if we were a couple of stupid kids. “Don’t you get it? She doesn’t have her jacket on and she’s only seven years old-”

“They could be anywhere,” Tookey said. “You can’t follow those tracks. They’ll be gone in the next drift.”

“What do you suggest?” Lumley yells, his voice high and hysterical. “If we go back to get the police, she’ll freeze to death! Francie and my wife!”

“They may be frozen already,” Tookey said. His eyes caught Lumley’s. “Frozen, or something worse.”

“What do you mean?” Lumley whispered. “Get it straight, goddamn it! Tell me!”

“Mr. Lumley,” Tookey says, “there’s something in the Lot-”

But I was the one who came out with it finally, said the word I never expected to say. “Vampires, Mr. Lumley. Jerusalem’s Lot is full of vampires. I expect that’s hard for you to swallow-”

He was staring at me as if I’d gone green. “Loonies,” he whispers. “You’re a couple of loonies.” Then he turned away, cupped his hands around his mouth, and bellowed,

“FRANCIE! JANEY!” He started floundering off again. The snow was up to the hem of his fancy coat.

I looked at Tookey. “What do we do now?”

“Follow him,” Tookey says. His hair was plastered with snow, and he did look a little bit loony. “I can’t just leave him out here. Booth. Can you?”

“No,” I says. “Guess not.”

So we started to wade through the snow after Lumley as best we could. But he kept getting further and further ahead. He had his youth to spend, you see. He was breaking the trail, going through that snow like a bull. My arthritis began to bother me something terrible, and I started to look down at my legs, telling myself: A little further, just a little further, keep goin’, damn it, keep goin’…

I piled right into Tookey, who was standing spread-legged in a drift. His head was hanging and both of his hands were pressed to his chest.

“Tookey,” I says, “you okay?”

“I’m all right,” he said, taking his hands away. “We’ll stick with him, Booth, and when he fags out he’ll see reason.”

We topped a rise and there was Lumley at the bottom, looking desperately for more tracks. Poor man, there wasn’t a chance he was going to find them. The wind blew straight across down there where he was, and any tracks would have been rubbed out three minutes after they was made, let alone a couple of hours.

He raised his head and screamed into the night:

“FRANCIE! JANEY! FOR GOD’S SAKE!” And you could hear the desperation in his voice, the terror, and pity him for it. The only answer he got was the freight-train wail of the wind. It almost seemed to be laughin’ at him, saying: I took them Mister New Jersey with your fancy car and camel’s-hair topcoat. I took them and I rubbed out their tracks and by morning I’ll have them just as neat and frozen as two strawberries in a deepfreeze…

“Lumley!” Tookey bawled over the wind. “Listen, you never mind vampires or boogies or nothing like that, but you mind this! You’re just making it worse for them! We got to get the-”

And then there was an answer, a voice coming out of the dark like little tinkling silver bells, and my heart turned cold as ice in a cistern.

“Jerry… Jerry, is that you?”

Lumley wheeled at the sound. And then she came, drifting out of the dark shadows of a little copse of trees like a ghost.

She was a city woman, all right, and right then she seemed like the most beautiful woman I had ever seen. I felt like I wanted to go to her and tell her how glad I was she was safe after all. She was wearing a heavy green pullover sort of thing, a poncho, I believe they’re called. It floated all around her, and her dark hair streamed out in the wild wind like water in a December creek, just before the winter freeze stills it and locks it in.

Maybe I did take a step toward her, because I felt Tookey’s hand on my shoulder, rough and warm. And still-how can I say it?-I yearned after her, so dark and beautiful with that green poncho floating around her neck and shoulders, as exotic and strange as to make you think of some beautiful woman from a Walter de la Mare poem.

“Janey!” Lumley cried.

“Janey!” He began to struggle through the snow toward her, his arms outstretched.

“No!” Tookey cried.

“No, Lumley!”

He never even looked… but she did. She looked up at us and grinned. And when she did, I felt my longing, my yearning turn to horror as cold as the grave, as white and silent as bones in a shroud. Even from the rise we could see the sullen red glare in those eyes. They were less human than a wolf’s eyes. And when she grinned you could see how long her teeth had become. She wasn’t human anymore. She was a dead thing somehow come back to life in this black howling storm.

Tookey made the sign of the cross at her. She flinched back… and then grinned at us again. We were too far away, and maybe too scared.

“Stop it!” I whispered. “Can’t we stop it?”

“Too late, Booth!” Tookey says grimly.

Lumley had reached her. He looked like a ghost himself, coated in snow like he was. He reached for her… and then he began to scream. I’ll hear that sound in my dreams, that man screaming like a child in a nightmare. He tried to back away from her, but her arms, long and bare and as white as the snow, snaked out and pulled him to her. I could see her cock her head and then thrust it forward-

“Booth!” Tookey said hoarsely. “We’ve got to get out of here!”

And so we ran. Ran like rats, I suppose some would say, but those who would weren’t there that night. We fled back down along our own backtrail, falling down, getting up again, slipping and sliding. I kept looking back over my shoulder to see if that woman was coming after us, grinning that grin and watching us with those red eyes.

We got back to the Scout and Tookey doubled over, holding his chest. “Tookey!” I said, badly scared. “What-”

“Ticker,” he said. “Been bad for five years or more. Get me around in the shotgun seat, Booth, and then get us the hell out of here.”

I hooked an arm under his coat and dragged him around and somehow boosted him up and in. He leaned his head back and shut his eyes. His skin was waxy-looking and yellow.

I went back around the hood of the truck at a trot, and I damned near ran into the little girl. She was just standing there beside the driver’s-side door, her hair in pigtails, wearing nothing but a little bit of a yellow dress.

“Mister,” she said in a high, clear voice, as sweet as morning mist, “won’t you help me find my mother? She’s gone and I’m so cold-”

“Honey,” I said, “honey, you better get in the truck. Your mother’s-”

I broke off, and if there was ever a time in my life I was close to swooning, that was the moment. She was standing there, you see, but she was standing on top of the snow and there were no tracks, not in any direction.

She looked up at me then, Lumley’s daughter Francie. She was no more than seven years old, and she was going to be seven for an eternity of nights. Her little face was a ghastly corpse white, her eyes a red and silver that you could fall into. And below her jaw I could see two small punctures like pinpricks, their edges horribly mangled.

She held out her arms at me and smiled. “Pick me up, mister,” she said softly. “I want to give you a kiss. Then you can take me to my mommy.”

I didn’t want to, but there was nothing I could do. I was leaning forward, my arms outstretched. I could see her mouth opening, I could see the little fangs inside the pink ring of her lips. Something slipped down her chin, bright and silvery, and with a dim, distant, faraway horror, I realized she was drooling.

Her small hands clasped themselves around my neck and I was thinking: Well, maybe it won’t be so bad, not so bad, maybe it won’t be so awful after a while-when something black flew out of the Scout and struck her on the chest. There was a puff of strange-smelling smoke, a flashing glow that was gone an instant later, and then she was backing away, hissing. Her face was twisted into a vulpine mask of rage, hate, and pain. She turned sideways and then… and then she was gone. One moment she was there, and the next there was a twisting knot of snow that looked a little bit like a human shape. Then the wind tattered it away across the fields.

“Booth!” Tookey whispered. “Be quick, now!” And I was. But not so quick that I didn’t have time to pick up what he had thrown at that little girl from hell. His mother’s Douay Bible.

That was some time ago. I’m a sight older now, and I was no chicken then. Herb Tooklander passed on two years ago. He went peaceful, in the night. The bar is still there, some man and his wife from Waterville bought it, nice people, and they’ve kept it pretty much the same. But I don’t go by much. It’s different somehow with Tookey gone.

Things in the Lot go on pretty much as they always have. The sheriff found that fellow Lumley’s car the next day, out of gas, the battery dead. Neither Tookey nor I said anything about it. What would have been the point? And every now and then a hitchhiker or a camper will disappear around there someplace, up on Schoolyard Hill or out near the Harmony Hill cemetery. They’ll turn up the fellow’s packsack or a paperback book all swollen and bleached out by the rain or snow, or some such. But never the people.

I still have bad dreams about that stormy night we went out there. Not about the woman so much as the little girl, and the way she smiled when she held her arms up so I could pick her up. So she could give me a kiss. But I’m an old man and the time comes soon when dreams are done.

You may have an occasion to be traveling in southern Maine yourself one of these days. Pretty part of the countryside. You may even stop by Tookey’s Bar for a drink. Nice place. They kept the name just the same. So have your drink, and then my advice to you is to keep right on moving north. Whatever you do, don’t go up that road to Jerusalem’s Lot.

Especially not after dark.

There’s a little girl somewhere out there. And I think she’s still waiting for her good-night kiss.

1977

Ur ( story ) … Stephen King

If you own an E-reader, avoid books by Stephen King. He’s a technical wordsmith, probably the result of “good” schooling, but he often lacks what it takes to create an interesting story. Ur, published for and seeming to serve as an elaborate plug for Amazon’s Kindle, is a perfect example.

The premise; a college English teacher buys a Kindle that offers nonexistence books from popular authors in alternative universes; has potential, but the tale Stephen King dents the fourth wall to crowbar it around is silly and illogical, especially when The Paradox Police arrive near the end.

my rating : 2 of 5

2009

video review : Cujo

Being trapped in a broken-down Pinto for several hours with a rabid dog trying to kill you every time you try to get out is bad. Having a dying kid with you is even worse. That’s the situation Fonna Trenton finds herself in one hot day.

The movie should be mostly that, but it isn’t. The car doesn’t break down, thus the suspense doesn’t begin, until pass the halfway point. Everything before comes across as a prelude involving Donna’s irrelevant marriage troubles.

my rating : 3 of 5

1983

video review : 1408

The set-up is interesting. A paranormal investigator named Mike Enslin receives an anonymous postcard in the mail about a particular room in New York City’s Dolphin Hotel. All the card says is “Don’t Enter 1408”. So, of course, he goes to the city and books an overnight reservation.

There’s a satisfyingly spooky scene featuring the hotel manager. He warns the man that the room is “evil”, begs him not to stay and talks as if he knows he’s in a Stephen King story. The plot falls apart from there, to the floor of horrid randomness, and keeps getting worse until checkout.

my rating : 1 of 5

2007

Full Dark No Stars ( book ) … Stephen King

The title is only half true. The stories of this Stephen King collection are indeed dark in nature; the set is bookended by tales of bloody spousal murder; but there are stars. It’s just that they’re normal people. They’re people who kill and harm other people, yes, but the author does his best to justify their actions by providing a method to their madness. Are his justifications successful? Not usually. There’s only one story in which I think the protagonist is justified and that’s the rape victim who seeks revenge on her Big Driver attacker. But their sides of the story are told. That’s the point.

It’s unfortunate those stories aren’t presented in a more interesting manner. The underlying concepts spark real suspense in the build-up, even the ridiculous Fair Extension, but the way Stephen King drones on and on in meticulous descriptions and backstory is more than enough to kill it. He’s an excellent writer when it comes to using words to tell a story, yes; possibly one of the best; but these stories lack anything interesting beyond that. There’s nothing clever or witty about them. No artistic depth. They’re just told. That might’ve been okay if the process weren’t so redundant.

The best parts of the Big Driver and 1922 stories; the rape and murder that should be their ending peaks; come closer to the beginning. After that, the plots just ramble along in boring epilogue. A Good Marriage gets the structure right, but the peak is unrealistic given everything that came before it. The normal caring protagonist, like the one in Big Driver, suddenly becomes as vicious as the man she’s up against. In this case though, it’s not a matter of retaliation, so her motive doesn’t make much sense. Not that it matters in the end. By that point, you’re just happy it’s all over.

my rating : 1 of 5

2010

Willa ( story ) … Stephen King

This story is best at the start as a man, stranded at a Wyoming train station with other derailed passengers, searches for his missing fiancée. Soon he wanders off into the darkness to look for her, despite the danger of being eaten by wolves or other creatures lurking in the night.

From there, a major revelation is revealed to both the reader and the character. That’s when the plot, which goes from mystery to folklore, starts to get silly. By the end, the title seems incomplete. The story is ultimately about a romantic bond between a woman and a man.

my rating : 2 of 5

2006

N ( story ) … Stephen King

The title is the first letter of a man’s name; a psychiatric patient who suffers from an extreme case of OCD. He fixates on counting, touching and ordering things; mundane objects like shoes and plates; in an effort to avoid odd numbers, which are a terrible thing, thus maintaining the order of the world. His mind didn’t always work that way, of course, and it’s how he got that way that gives the story its eerie undertone.

I like that it’s written not as a traditional narrative but a series of case notes, news articles, personal letters and emails from the perspective of four characters who ultimately have a lot in common. What I don’t like is that most of those manuscripts ramble on with meticulous detail in signature Stephen King fashion. In the end, it’s a novella that, though interesting, could’ve been much better if it were more concise.

my rating : 3 of 5

2008

video review : Carrie

Naked high school girls showering after a sweaty game of volleyball grabs your attention in the first few minutes. “Creepy” Carrie is far from the sexiest among them, but she is cute in an unobtrusive way. The fact that she’s constantly mistreated by almost everyone around her, including her manic Mama, makes you root for her. It’s when she’s invited to the prom by Tommy Ross, one of the cutest coolest boys in the school, which she relunctantly accepts, that things start to go really bad for her.

It’s a sad story but never to the point of maudlinism, even when Carrie’s sadness forces her to tears. That’s because she possesses a power that more than makes up for her social inadequacies. She can move and physically affect things with her mind; she can close windows and break mirrors; if she concentrates hard enough. It’s what known as telekinesis, a phenomenon she herself doesn’t fully understand. All she knows is that it tends to happen, rather inadvertently, when people make her mad.

The final fifteen minutes or so before the ending credits, especially the view-violating epilogue that makes up the final three minutes, are unnecessary. From both a narrative and an artistic point of view, the movie should end just after the prom, which is the obvious climax in the world of a high school student who cares about nothing more than fitting in with the popular crowd. With that said, the ending excess isn’t enough to ruin what remains an endearing story about a very special girl.

my rating : 4 of 5

1976

a Stephen King story from The Atlantic : Herman Wouk Is Still Alive

Instead of going out for a bottle of Orange Driver to celebrate with, she pays off the MasterCard, which has been maxed like forever. Then calls Hertz and asks a question. Then calls her friend Jasmine, who lives in North Berwick, and tells her about the Pick-4. Jasmine screams and says, “Girl, you’re rich!”

If only. Brenda explains how she paid off the credit card so she can rent a Chevy Express if she wants to. It’s a van that seats nine, that’s what the Hertz girl told her. “We could get all the kids in there and drive up to Mars Hill. See your folks and mine. Show off the grandchildren. Squeeze ’em for a little more dough. What do you think?”

Jasmine is dubious. The glorified shack her folks call home doesn’t have room, and she wouldn’t want to stay with them even if it did. She hates those two. With good reason, Brenda knows; her own father broke Jasmine in at fifteen. Her mother knew what was going on and did nothing. When Jasmine went to her in tears, her ma said, “You got nothing to worry about, he’s had his nuts cut.”

Jas married Mitch Robicheau to get away from them, and now, three men, four kids, and eight years later, she’s on her own. And on welfare, although she gets sixteen hours a week at the Roll Around, handing out skates and making change for the video arcade, where the machines take only special tokens. They let her bring her two youngest. Delight sleeps in the office and Truth, her three-year-old, wanders around in the arcade hitching at his diapers. He doesn’t get into too much trouble, although last year he got head lice and the two women had to shave all his hair off. How he howled.

“There’s six hundred left over after I paid off the credit balance,” Brenda says. “Well, four hundred if you count the rental, only I don’t, because I can put that on MasterCard. We could stay at the Red Roof, watch Home Box. It’s free. We can get takeout from downstreet and the kids can swim in the pool. What do you say?”

From behind her comes yelling. Brenda raises her voice and screams, “Freddy, you stop teasing your sister and give that back!” Then, oh goody, their squabbling wakes up the baby. Either that or Freedom has messed in her diapers and awakened herself. Freedom always messes in her diapers. To Brenda it seems like Free is making poop her life’s work. Takes after her father that way.

“I suppose …” Jasmine says, drawing suppose out to four syllables. Maybe five.

“Come on, girl! Road trip! Get with the program! We take the bus down to the Jetport and rent the van. Three hundred miles, we can be there in four hours. The girl says they can watch DVDs. The Little Mermaid and all that good stuff.”

“Maybe I could get some of that government money from my ma before it’s all gone,” Jasmine says thoughtfully. Her brother Tommy died the year before, in Afghanistan. IED. Her ma and dad got eighty thousand out of it. Her ma has promised her some, although not when the old man is in hearing distance of the phone. Of course it may be gone already. Probably is. She knows Mr. Romance bought a Yamaha rice rocket, although what he wants with a thing like that at his age, Jasmine has no idea. And she knows things like government money are mostly a mirage. This is something they both know. Every time you see bright stuff, somebody turns on the rain machine. The bright stuff is never colorfast.

“Come on,” Brenda says. She has fallen in love with the idea of loading up the van with kids and her best (her only) friend from high school, who ended up living just one town over. Both of them on their own, seven kids between them, too many lousy men in the rearview, but sometimes they still have a little fun.

She hears a thunk sound. Freddy starts to scream. Glory has whopped him in the eye with an action figure.

“Glory you stop that or I’ll tear you a new one!” Brenda screams.

“He won’t give back my Powerpuff!” Glory shrieks, and she starts to cry. Now they’re all crying—Freddy, Glory, and Freedom—and for a moment grayness creeps over Brenda’s vision. She’s seen a lot of that grayness lately. Here they are in a three-room third-floor apartment, no guy in the picture (Tim, the latest in her life, took off six months ago), living pretty much on noodles and Pepsi and that cheap ice cream they sell at Walmart, no air-conditioning, no cable TV, she had a job at the Quik-Flash store but the company went busted and now the store’s an On the Run and the manager hired some Taco Paco to do her job because Taco Paco can work twelve or fourteen hours a day. Taco Paco wears a do-rag on his head and a nasty little mustache on his upper lip and he’s never been pregnant. Taco Paco’s job is to get girls pregnant. They fall for that little mustache and then boom, the line in the little drugstore testing gadget turns blue and here comes another one, just like the other one.

Brenda has personal experience; she tells people she knows who Freddy’s father is, but she really doesn’t, she had a few drunk nights when they all looked good, and really, come on, how is she supposed to look for a job anyway? She’s got these kids. What’s she supposed to do, leave Freddy to mind Glory and take Freedom to the goddamn job interviews? Sure, that’ll work. And what is there, besides drive-up-window girl at Mickey D’s or the Booger King? Portland has a couple of strip clubs, but wide loads like her don’t get that kind of work, and everyone else is broke.

She reminds herself she hit the lottery. She reminds herself they could be in a couple of air-conditioned rooms tonight at the Red Roof—three, even! Why not? Things are turning around!

“Brennie?” Her friend sounds more doubtful than ever. “Are you still there?”

“Yeah,” she says. “Come on, girl, I’m approved. The Hertz chick says the van is red.” She lowers her voice and adds: “Your lucky color.”

“Did you pay off the credit card online? How’d you do that?” Jasmine knows what happened to Brenda’s laptop. Freddy and Glory got fighting last month and knocked Brenda’s laptop off the bed. It fell on the floor and broke.

“I used the one at the library.” She says it the way she grew up in Mars Hill saying it: liberry. “I had to wait awhile to get on, but it’s worth it. It’s free. So what do you say?”

“Maybe we could get a bottle of Allen’s,” her friend says. Jasmine loves that Allen’s Coffee Brandy, when she can get it. In truth, Jasmine loves anything when she can get it.

“Apple-solutely,” Brenda says. “And a bottle of Driver for me. But I won’t drink while I’m behind the wheel, Jas. You can, but I’ll wait. I have to keep my license. It’s about all I got left.”

“Can you really get any money out of your folks, do you think?”

Brenda tells herself that once they see the kids—assuming the kids can be bribed (or intimidated) into good behavior—she can. “But not a word about the lottery,” she says.

“No way,” Jasmine says. “I was born at night but it wasn’t last night.”

They yuk at this one, an oldie but a goodie.

“So what do you think?”

“I’ll have to take Eddie and Rosellen out of school …”

“BFD,” Brenda says. “So what do you think, girl?”

After a long pause on the other end, Jasmine says, “Road trip!”

“Road trip!” Brenda hollers back.

Then they are chanting it while the three kids bawl in Brenda’s Sanford apartment and at least one (maybe two) is bawling in Jasmine’s North Berwick apartment. These are the fat women nobody wants to see when they’re on the streets, the ones no guy wants to pick up in the bars unless the hour is late and the mood is drunk and there’s nobody better in sight. What men think when they’re drunk—Brenda and Jasmine both know this—is that thunder thighs are better than no thighs at all. They went to high school together in Mars Hill and now they’re downstate and they help each other when they can. They are the fat women nobody wants to see, they have a litter of children between them, and they are chanting Road trip, road trip like a couple of cheerleading fools. On a September morning, already hot at eight-thirty, this is the way things happen. It’s never been any different.

Phil Henreid is seventy-eight now, and Pauline Enslin is seventy-five. They’re both skinny. They both wear spectacles. Their hair, white and thin, blows in the breeze. They’ve paused at a rest area on I-95 near Fairfield, which is about twenty miles north of Augusta. The rest-area building is barnboard, and the adjacent bathrooms are brick. They’re good-looking bathrooms. Modest bathrooms. There’s no odor. Phil, who lives in Maine and knows this rest area well, would never have proposed a picnic here in the summertime. When the traffic on the interstate swells with out-of-state vacationers, the Turnpike Authority brings in a line of plastic Port-O-Sans, and this pleasant grassy area stinks like hell on New Year’s Eve. But now the Port-O-Sans are in storage somewhere, and the rest area is nice.

Pauline puts a checked cloth on the initial-scarred picnic table standing in the shade of an old oak, and anchors it with a wicker picnic basket against a slight warm breeze. From the basket she takes sandwiches, potato salad, melon wedges, and two slices of coconut-custard pie. She also has a large glass bottle of red tea. Ice cubes clink cheerfully inside.

“If we were in Paris, we’d have wine,” Phil says.

“In Paris, we never had another sixty miles to drive on the turnpike,” she replies. “That tea is cold and it’s fresh. You’ll have to make do.”

“I wasn’t carping,” he says, and lays an arthritis-swollen hand over hers (which is also swollen, although marginally less so). “This is a feast, my dear.”

They smile into each other’s used faces. Although Phil has been married three times (and has scattered five children behind him like confetti) and Pauline has been married twice (no children, but lovers of both sexes in the dozens), they still have quite a lot between them. Much more than a spark. Phil is both surprised and not surprised. At his age—late, but not quite yet last call—you take what you can and are happy to get it. They are on their way to a poetry festival at the University of Maine’s Orono campus, and while the compensation for their joint appearance isn’t huge, it’s perfectly adequate. Since he has an expense account, Phil has splurged and rented a Cadillac from Hertz at the Portland Jetport, where he met her plane. Pauline jeered at this, said she always knew he was a plastic hippie, but she does it gently. He wasn’t a hippie, but he was a genuine whatever-he-was, and she knows it. As he knows that her osteoporotic bones have enjoyed the ride.

Now, a picnic. Tonight they’ll have a catered meal, but the food will be a lukewarm, sauce-covered mess o’ mystery supplied by the cafeteria in one of the college commons. “Beige food” is what Pauline calls it. Visiting-poet food is always beige, and in any case it won’t be served until eight o’clock. With some cheap yellowish-white wine seemingly created to saw at the guts of semi-retired alcohol abusers such as themselves. This meal is nicer, and iced tea is fine. Phil even indulges the fantasy of leading her by the hand to the high grass behind the bathrooms once they have finished eating, like in that old Van Morrison song, and—

Ah, but no. Elderly poets whose sex drives are now permanently stuck in first gear should not chance such a potentially ludicrous site of assignation. Especially poets of long, rich, and varied experience, who now know that each time is apt to be largely unsatisfactory, and each time may well be the last time. Besides, Phil thinks, I have already had two heart attacks. Who knows what’s up with her?

Pauline thinks, Not after sandwiches and potato salad, not to mention custard pie. But perhaps tonight. It is not out of the question. She smiles at him and takes the last item from the hamper. It is a New York Times, bought at the same Augusta convenience store where she got the rest of the picnic things, checked cloth and iced-tea bottle included. As in the old days, they flip for the Arts section. In the old days, Phil—who won the National Book Award for Burning Elephants in 1970—always called tails and won far more times than the odds said he should. Today he calls heads … and wins again.

“Why, you snot!” she cries, and hands it over.

They eat. They read the divided paper. At one point she looks at him over a forkful of potato salad and says, “I still love you, you old fraud.”

Phil smiles. The wind blows the gone-to-seed dandelion puff of his hair. His scalp shines gauzily through. He’s not the young man who once came roistering out of Brooklyn, broad-shouldered as a longshoreman (and just as foulmouthed), but Pauline can still see the shadow of that man, who was so full of anger, despair, and hilarity.

“Why, I love you, too, Paulie,” he says.

“We’re a couple of old crocks,” she says, and bursts into laughter. Once she had sex with a king and a movie star at pretty much the same time on a balcony while “Maggie May” played on the gramophone, Rod Stewart singing in French. Now the woman The New York Times once called America’s greatest living female poet lives in a walk-up in Queens. “Doing poetry readings in tank towns for dishonorable honorariums and eating alfresco in rest areas.”

“We’re not old,” he says, “we’re young, ma bébé.”

“What in the world are you talking about?”

“Look at this,” he says, and holds out the first page of the Arts section. She takes it and sees a photograph. It’s a dried-up string of a man wearing a straw hat and a smile.

As she looks at that old, seamed face beneath the rakishly tilted straw hat, Pauline feels the sudden sting of tears. “The body weakens but the words never do,” she says. “That’s lovely.”

“Have you ever read him?” Phil asks.

“Marjorie Morningstar, in my youth. It’s an annoying hymn to virginity, but I was swept away in spite of myself. Have you?”

“I tried Youngblood Hawke, but couldn’t finish it. Still … he’s in there pitching. And he’s old enough to be our father.” He folds the paper and puts it into the picnic basket. Below them, light traffic on the turnpike runs beneath a high September sky full of fair-weather clouds. “Before we get back on the road, do you want to do swapsies? Like in the old days?”

She thinks about it, then nods. Many years have passed since she listened to someone else read one of her poems, and the experience is always a little dismaying—like having an out-of-body experience—but why not? They have the rest area to themselves. “In honor of Herman Wouk, who’s still in there pitching. My work folder’s in the front pocket of my carrybag.”

“You trust me to go through your things?”

She gives him her old slanted smile, then stretches into the sun with her eyes closed. Relishing the heat. Soon the days will turn cold, but now there is heat. “You can go through my things all you want, Philip.” She opens one eye in a reverse wink that is amusingly seductive. “Explore to your heart’s content.”

“I’ll keep that in mind,” he says, and goes back to the Cadillac he has rented for them.

Poets in a Cadillac, she thinks. The very definition of absurdity. For a moment she watches the cars rush by. Then she picks up the Arts section and looks again at the narrow, smiling face of the old scribbler. Still alive. Perhaps at this very moment looking up at the high blue September sky, with his notebook open on a patio table and a glass of Perrier (or wine, if his stomach will still stand it) near to hand.

If there is a God, Paulie Enslin thinks, she can occasionally be very generous.

She waits for Phil to come back with her work folder and one of the steno pads he favors for composition. They will play swapsies. Tonight they may play other games. Once again she tells herself, It is not out of the question.

Everything is digital. There’s a satellite radio with a GPS screen above it. When she backs up, the GPS turns into a TV monitor, so you can see what’s behind you. Everything on the dashboard shines, that new-car smell fills the interior, and why not, with only seven hundred and fifty miles on the odometer? She has never in her life been behind the wheel of a motor vehicle with such low mileage. You can push buttons on the control-stalk to show you your average speed, how many miles per gallon you’re getting, and how many gallons you’ve got left. The engine makes hardly any noise at all. The seats up front are twin buckets, upholstered in bone-white material that looks like leather. The shocks are like butter.

In back is a pop-down TV screen with a DVD player. The Little Mermaid won’t work because Truth, Jasmine’s three-year-old, spread peanut butter all over the disc at some point, but they are content with Shrek, even though all of them have seen it like a billion times. The thrill is watching it while they’re on the road! Driving! Freedom is asleep in her car seat between Freddy and Glory; Delight, Jasmine’s six-month-old, is asleep in Jasmine’s lap, but the other five cram together in the two back seats, watching, entranced. Their mouths are hanging open. Jasmine’s Eddie is picking his nose, and Eddie’s older sister, Rosellen, has got drool on her sharp little chin, but at least they are quiet and not beating away at each other for once. They are hypnotized.

Brenda should be happy, she knows she should. The kids are quiet, the road stretches ahead of her like an airport runway, she’s behind the wheel of a brand-new van, and the traffic is light, especially once they leave Portland behind. The digital speedometer reads 70, and this baby hasn’t even broken a sweat. Nonetheless, that grayness has begun to creep over her again. The van isn’t hers, after all. She’ll have to give it back. A foolish expense, really, because what’s at the far end of this trip, up in Mars Hill? Food brought in from the Round-Up Restaurant, where she used to work when she was in high school and still had a figure. Hamburgers and fries covered with plastic wrap. The kids splashing in the pool before and maybe after. At least one of them will get hurt and bawl. Maybe more. And Glory will complain that the water is too cold, even if it isn’t. Glory always complains. She will complain her whole life. Brenda hates that whining and likes to tell Glory it’s her father coming out … but the truth is, the kid gets it from both sides. Poor kid. All of them, really. All poor kids, headed into poor lives.

She looks to her right, hoping Jas will say something funny and cheer her up, and is dismayed to see that Jasmine is crying. Silent tears well up in her eyes and shine on her cheeks. In her lap, baby Delight sleeps on, sucking one of her fingers. It’s her comfort-finger, and all blistered down the inside. Once, Jas slapped her good and hard when she saw Dee sticking it in her mouth, but what good is slapping a kid that’s only six months old? Might as well slap a door. But sometimes you do it. Sometimes you can’t help it. Sometimes you don’t want to help it. Brenda has done it herself.

“What’s wrong, girl?” Brenda asks.

“Nothing. Never mind me, just watch your driving.”

Behind them, Donkey says something funny to Shrek, and some of the kids laugh. Not Glory, though; she’s nodding off.

“Come on, Jas. Tell me. I’m your friend.”

“Nothing, I said.” Jas leans over the sleeping infant. Delight’s baby seat is on the floor. Resting in it on a pile of diapers is the bottle of Allen’s they stopped for in South Portland, before hitting the turnpike. Jas has only had a couple of sips, but this time she takes two good long swallows before putting the cap back on. The tears are still running down her cheeks. “Nothing. Everything. Comes to the same either way you say it, that’s what I think.”

“Is it Tommy? Is it your bro?”

Jas laughs angrily. “They’ll never give me a cent of that money, who’m I kidding? Ma’ll blame it on Dad because that’s easier for her, but she feels the same. It’ll mostly be gone, anyway. What about you? Will your folks really give you something?”

“Sure, I think so.” Well. Yeah. Probably. Like forty dollars. A bag and a half’s worth of groceries. Two bags if she uses the coupons in Uncle Henry’s Swap or Sell It Guide. Just the thought of flipping through that raggy little cheap magazine—the poor people’s Bible—and getting the ink on her fingers causes the grayness around her to thicken. The afternoon is beautiful, more like summer than September, but a world where you have to depend on Uncle Henry’s is a gray world. Brenda thinks, How did we end up with all these kids? Wasn’t I letting Mike Higgins cop a feel of me out behind the metal shop just yesterday?

“Bully for you,” Jasmine says, and snorks back tears. “My folks, they’ll have three new gasoline toys in the dooryard and then plead poverty. And do you know what my dad’ll say about the kids? ‘Don’t let ’em touch anything,’ that’s what he’ll say.”

“Maybe he’ll be different,” Brenda says. “Better.”

“He’s never different and he’s never better,” Jasmine says, “and he never will be.”

In the backseat, Rosellen is drifting off. She tries to put her head on her brother Eddie’s shoulder and he punches her in the arm. She rubs it and begins to snivel, but pretty soon she’s watching Shrek again. The drool is still on her chin. Brenda thinks it makes her look like an idiot, which she pretty close to is.

“I don’t know what to say,” Brenda says. “We’ll have some fun, anyway. Red Roof, girl! Swimming pool!”

“Yeah, and some guy knocking on the wall at one in the morning, telling me to shut my kid up. Like, you know, I want Dee awake in the middle of the night because all those stinkin’ teeth are coming in at once.”

She takes another slug from the coffee-brandy bottle, then holds it out to Brenda. Brenda knows better than to take it, to risk her license … but no cops are in sight and if she did lose her ticket, how much would she really be out? The car was Tim’s, he took it when he left, and it was a half-dead beater anyway, a Bondo-and-chicken-wire special. No great loss there. Besides, there’s that grayness. She takes the bottle and tips it. Just a little sip, but the brandy’s warm and nice, a shaft of dark sunlight, so she takes another one.

“They’re closing the Roll Around at the end of the month,” Jasmine says, taking the bottle back.

“Jassy, no!”

“Jassy yes.” She stares straight ahead at the unrolling road. “Jack finally went broke. The writing’s been on the wall since last year. So there goes that ninety a week.” She drinks. In her lap, Delight stirs, then goes back to sleep with her comfort-finger plugged in her gob. Where, Brenda thinks, some boy like Mike Higgins will want to put his dick not all that many years from now. And she’ll probably let him. I did. Jas did too. It’s just how things go.

Behind them Princess Fiona is now saying something funny, but none of the kids laugh. They’re getting glassy, even the older kids. Eddie and Freddy, names like a TV-sitcom joke.

“The world is gray,” Brenda says. She didn’t know she was going to say those words until she hears them come out of her mouth.

Jasmine looks at her, surprised. “That’s right,” she says. “Now you’re getting with the program.”

Brenda says, “Pass me that bottle.”

Jasmine does. Brenda drinks some more, then hands it back. “Okay, enough of that.”

Jasmine gives her her old sideways grin, the one Brenda remembers from study hall on Friday afternoons. It looks strange, below her wet cheeks and bloodshot eyes. “You sure?”

Brenda doesn’t reply, but she pushes the accelerator a little deeper with her foot. Now the digital speedometer reads 80.

All at once she feels shy, afraid to hear her words coming out of Phil’s mouth, sure they will sound booming yet false, like dry thunder. But she has forgotten the difference between his public voice—declamatory and a little corny, like the voice of a movie attorney in a summing-up-to-the-jury scene—and the one he uses when he’s with just a friend or two (and hasn’t had anything to drink). It is a softer, kinder voice, and she is pleased to hear her poem coming out of his mouth. No, more than pleased. She is grateful. He makes it sound far better than it is.

Shadows print the road

with black lipstick kisses.

Decaying snow in farmhouse fields

shines like cast-off bridal dresses.

The rising mist turns to gold dust.

The clouds boil apart and a phantom disc

seems to race behind them.

It bursts through!

For five seconds it could be summer

and I seventeen with flowers

in the lap of my dress.He puts the sheet down. She looks at him, smiling a little, but anxious. He nods his head. “It’s fine, dear,” he says. “Fine enough. Now you.”

She opens the steno pad, finds what appears to be the last poem, and pages through four or five scribbled drafts. She knows how he works, and she goes on until she comes to a version not in mostly illegible cursive but in small neat printing. She shows it to him. Phil nods, then turns to look at the turnpike. All of this is very nice, but they will have to go soon. They don’t want to be late.

He sees a bright-red van coming. It’s going fast.

She begins.

Yes, she thinks, that’s just about right. Thanksgiving for fools.

Freddy will go for a soldier and fight in foreign lands, the way Jasmine’s brother Tommy did. Jasmine’s boys, Eddie and Truth, will do the same. They’ll own muscle cars when and if they come home, and if gas is still available twenty years from now. And the girls? They’ll go with boys. They’ll give up their virginity while game shows play on TV. They’ll have babies and fry meat in skillets and put on weight, same as she and Jasmine did. They’ll smoke a little dope and eat a lot of ice cream—the cheap stuff from Walmart. Maybe not Rosellen, though. Something is wrong with Rosellen. She’ll need to go to the special-ed classes. She’ll still have drool on her sharp little chin when she’s in the eighth grade, same as now. The seven kids will beget seventeen, and the seventeen will beget seventy, and the seventy will beget two hundred. She can see a ragged fool’s parade marching into the future, some wearing jeans that show the ass of their underwear, some wearing heavy-metal T-shirts, some wearing gravy-spotted waitress uniforms, some wearing stretch pants from Kmart that have little MADE IN PARAGUAY tags sewn into the seams of the roomy seats. She can see the mountain of Fisher-Price toys they will own and that will later be sold at yard sales (which was where most were bought in the first place). They will buy the products they see on TV and go in debt to the credit-card companies, as she did … and will again, because the Pick-4 was a fluke and she knows it. Worse than a fluke, really: a tease. Life is basically a rusty hubcap lying in a ditch at the side of the road, and life goes on. She will never again feel like she’s sitting in the cockpit of a jet fighter. This is as good as it gets. Her ship will not come in. There are no boats for nobody, and no camera is filming her life. This is reality, not a reality show.

Shrek is over and all the kids are asleep, even Eddie. Rosellen’s head is once more on Eddie’s shoulder. She’s snoring like an old woman. She has red marks on her arms, because sometimes she can’t stop scratching herself.

Jasmine screws the cap on the bottle of Allen’s and drops it back into the baby seat in the footwell. In a low voice she says, “When I was five, I believed in unicorns.”

“So did I,” Brenda says. She looks at Jasmine. “I wonder how fast this thing goes.”

Jasmine looks at the road ahead. They flash past a blue sign that says REST AREA 1 MI. She sees no traffic northbound; both lanes are entirely theirs. “Let’s find out,” Jasmine says.

The numbers on the speedometer rise from 80 to 85. Then 87. There’s still some room left between the accelerator pedal and the floor. All the kids are sleeping.

Here is the rest area, coming up fast. Brenda sees only one car in the parking lot. It looks like a fancy one, a Lincoln or maybe a Cadillac. I could have rented one of those, she thinks. I had enough money but too many kids. Couldn’t fit them all in. Story of her life, really.

She looks away from the road. She looks at her old friend from high school, who ended up living just one town away. Jasmine is looking back at her. The van, now doing almost a hundred miles an hour, begins to drift.

Jasmine gives a small nod and then lifts Dee, cradling the baby against her big breasts. Dee’s still got her comfort-finger in her mouth.

Brenda nods back. Then she pushes down harder with her foot, trying to find the van’s carpeted floor. It’s there, and she lays the accelerator pedal softly against it.

He reaches out and grabs her shoulder with his bony hand, startling her. She looks up from his poem and sees him staring at the turnpike. His mouth is open and behind his glasses his eyes appear to be bulging out almost far enough to touch the lenses. She follows his gaze in time to see a red van slide smoothly from the travel lane into the breakdown lane and from the breakdown lane across the rest-area entrance ramp. It doesn’t turn in. It’s going far too fast to turn in. It crosses, doing at least ninety miles an hour, and plows onto the slope just below them, where it hits a tree. She hears a loud, toneless bang and the sound of breaking glass. The windshield disintegrates; glass pebbles sparkle for a moment in the sun and she thinks—blasphemously—beautiful.

The tree shears the van into two ragged pieces. Something—Phil Henreid can’t bear to believe it’s a child—is flung high into the air and comes down in the grass. Then the van’s gas tank begins to burn, and Pauline screams.

He gets to his feet and runs down the slope, vaulting over the shakepole fence like the young man he once was. These days his failing heart is seldom far from his mind, but as he runs down to the burning pieces of the van, he never even thinks of it.

Cloud-shadows roll across the field, then across the woods beyond. Wildflowers nod their heads.

He stops twenty yards from the gasoline funeral pyre, the heat baking his face. He sees what he knew he would see—no survivors—but he never imagined so many non-survivors. He sees blood on the grass. He sees a shatter of taillight glass like a patch of strawberries. He sees a severed arm caught in a bush. In the flames he sees a melting baby seat. He sees shoes.

Pauline comes up beside him. She’s gasping for breath. The only thing wilder than her hair are her eyes.

“Don’t look,” he says.

“What’s that smell? Phil, what’s that smell?”

“Burning gas and rubber,” he says, although that’s probably not the smell she’s talking about. “Don’t look. Go back and—do you have your cell phone?”

“Yes, of course I have it—”

“Go back and call 911. Don’t look at this. You don’t want to see this.”

He doesn’t want to see it either, but cannot look away. How many? He can see the bodies of at least three children and one adult—probably a woman, but he can’t be sure. Yet so many shoes … and all the clothes … he can see a DVD package …

“What if I can’t get through?” she asks.

He points to the smoke. Then to the three or four cars that are already pulling over. “Getting through won’t matter,” he says, “but try.”

She starts to go, then turns back. She’s crying. “Phil … how many?”

“I don’t know. A lot. Go on, Paulie. Some of them might still be alive.”

“You know better,” she says through her sobs. “Damn thing was going too fast.”

She begins trudging back up the hill. Halfway to the rest-area parking lot (more cars are pulling in now), a terrible idea crosses her mind and she looks back, sure she will see her old friend and lover lying in the grass himself, perhaps clutching his chest, perhaps unconscious. But he’s on his feet, cautiously circling the blazing left half of the van. As she watches, he takes off his natty sport jacket with the patches on the elbows. He kneels and covers something with it. Either a person or a part of a person. Then he goes on.

Climbing the hill, she thinks that all their efforts to make beauty out of words is an illusion. Or a joke played on children who have selfishly refused to grow up. Yes, probably that. Children like that, she thinks, deserve to be pranked.

As she reaches the parking lot, still gasping for breath, she sees the Times Arts section flipping lazily through the grass on the breath of a light breeze and thinks, Never mind. Herman Wouk is still alive and writing a book about God’s language. Herman Wouk believes that the body weakens, but the words never do. So that’s all right, isn’t it?

A man and a woman rush up. The woman raises her own cell phone and takes a picture with it. Pauline Enslin observes this without much surprise. She supposes the woman will show it to friends later. Then they will have drinks and a meal and talk about the grace of God. God’s grace looks intact every time it’s not you.

“What happened?” the man shouts into her face.

Down below them a skinny old poet is happening. He’s now naked to the waist. He has taken off his shirt to cover one of the other bodies. His ribs are a stack outlined against white skin. He kneels and spreads the shirt. He raises his arms into the sky, then lowers them and wraps them around his head.

Pauline is also a poet, and as such feels capable of answering the man in the language God speaks.

“What the fuck does it look like?” she says.

2011

theatlantic.com